India slips four places to rank 111 out of 125 countries in Global Hunger Index (GHI) 2023

Previously, India ranked 107 out of 121 countries in 2022. GHI is published by Concern Worldwide (international humanitarian organization) and Welthungerhilfe (private aid organisation in Germany).

GHI is used to measure and track hunger at global, regional, and national levels. It uses four parameters to determine its score.

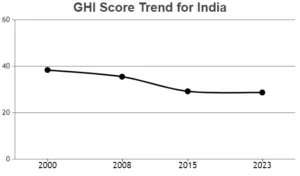

In the 2023 Global Hunger Index, India ranks 111th out of the 125 countries with sufficient data to calculate 2023 GHI scores. With a score of 28.7 in the 2023 Global Hunger Index, India has a level of hunger that is serious.

Key findings of GHI

- India’s ranking is based on a GHI score of 28.7.

- Highest child wasting rate (under five age who have low weight for their height) in world at 18.7 percent,

reflecting acute undernutrition. - Rate of undernourishment (caloric intake is insufficient) stood at 16.6 percent and under-five mortality (children who die before their fifth birthday) at 3.1 percent.

- Since 2015, worldwide progress against hunger remains largely standstill.

- South Asia and Africa (South of Sahara) are the world regions with highest hunger levels

However, Ministry of Women and Child Development (MoWCD) questioned GHI and called it a flawed measure of hunger that doesn’t reflect India’s true position.

Objections raised by MoWCD on GHI

- 3 out of 4 indicators of GHI are related to health of children and cannot be representative of entire population.

- 4th indicator (Undernourishment) is based on telephone-based opinion poll conducted on a very small sample size of 3000.

ABOUT THE GLOBAL HUNGER INDEX SCORES

The Global Hunger Index (GHI) is a tool for comprehensively measuring and tracking hunger at global, regional, and national levels. GHI scores are based on the values of four component indicators:

Undernourishment: the share of the population with insufficient caloric intake.

![]() Child stunting: the share of children under age five who have low height for their age, reflecting chronic undernutrition.

Child stunting: the share of children under age five who have low height for their age, reflecting chronic undernutrition.

Child wasting: the share of children under age five who have low weight for their height, reflecting acute undernutrition.

![]()

Child mortality: the share of children who die before their fifth birthday, partly reflecting the fatal mix of inadequate nutrition and unhealthy environments.

Based on the values of the four indicators, a GHI score is calculated on a 100-point scale reflecting the severity of hunger, where 0 is the best possible score (no hunger) and 100 is the worst. Each country’s GHI score is classified by severity, from low to extremely alarming.

Frequently Asked Questions

The Global Hunger Index (GHI) is a peer-reviewed report, published on an annual basis by Concern Worldwide and Welthungerhilfe. The GHI is a tool designed to comprehensively measure and track hunger at global, regional, and national levels, reflecting multiple dimensions of hunger over time. The report aims to raise awareness and understanding of the struggle against hunger, provide a way to compare levels of hunger between countries and regions, and call attention to those areas of the world where hunger levels are highest and where the need for additional efforts to eliminate hunger is greatest.

Each country’s GHI score is calculated based on a formula that combines four indicators that together capture the multidimensional nature of hunger:

- Undernourishment: the share of the population whose caloric intake is insufficient;

- Child stunting: the share of children under the age of five who have low height for their age, reflecting chronic undernutrition;

- Child wasting: the share of children under the age of five who have low weight for their height, reflecting acute undernutrition; and

- Child mortality: the share of children who die before their fifth birthday, reflecting in part the fatal mix of inadequate nutrition and unhealthy environments.

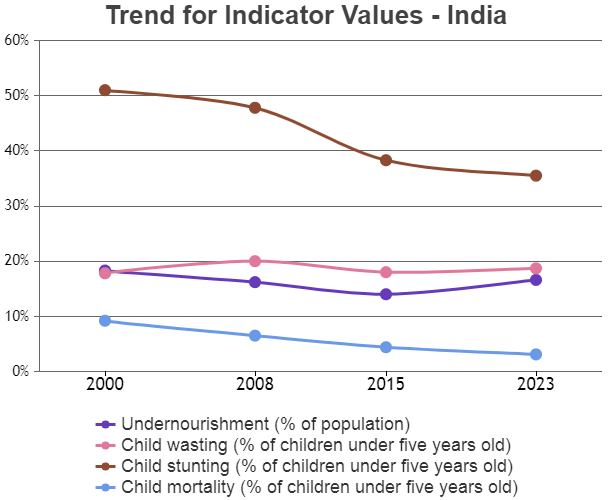

India’s 2023 GHI score is 28.7, considered serious according to the GHI Severity of Hunger Scale. This is a slight improvement from its 2015 GHI score of 29.2, also considered serious, and shows considerable improvement relative to its 2000 and 2008 GHI scores of 38.4 and 35.5, respectively, both considered alarming. India is ranked 111th out of 125 countries included in the ranking in the 2023 GHI report. India’s child wasting rate, at 18.7 percent, is the highest child wasting rate in the report; its child stunting rate is 35.5 percent; its prevalence of undernourishment is 16.6 percent; and its under-five mortality rate is 3.1 percent.

The 2023 GHI report provides comparisons between countries for 2000, 2008, 2015, and 2023 GHI scores and indicator values. It is not valid, however, to compare the data and ranking published in the 2023 GHI report with the data and ranking published in the 2022 GHI report, or any other past reports. This is because each year, the data are revised, the set of countries included in the ranking changes, and the methodology may also be revised (see Appendix A of the 2023 GHI or the explanation of the methodology on our website). Consequently, given the nature of the data underlying the calculation of GHI scores, the 2000, 2008, 2015, and 2023 GHI scores and indicator values published in the 2023 GHI report are the only historical data that can currently be used for valid comparisons over time.

The following values for the GHI component indicators were used to calculate India’s 2023 GHI score: The prevalence of undernourishment value is 16.6 percent, as reported in the 2023 State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (SOFI) report. The child mortality value is 3.1 percent, as reported in the United Nations Inter-Agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation’s (UN IGME) latest report, published in January 2023. The child stunting value is 35.5 percent, and the child wasting value is 18.7 percent; these are the values from India’s National Family Health Survey (2019–2021) (NFHS-5) as reported in the Joint Malnutrition Estimates Joint Data Set Including Survey Estimates (2023 edition).

In the compilation of the stunting and wasting values, we prioritize and use survey estimates that have been vetted for inclusion in the Joint Malnutrition Estimates and/or the WHO Global Database on Child Growth and Malnutrition, wherever possible. The GHI uses the same data sources for all countries to calculate the respective country scores. This ensures that all the rates used have been produced using comparable methodologies. Introducing exceptions to this process for any country or countries would compromise the comparability of the results and the ranking.

India has demonstrated significant political will to transform the food and nutrition landscape. Some examples are the National Food Security Act, Poshan Abhiyan (National Nutrition Mission), PM Garib Kalyan Yojna and National Mission for Natural Farming. However, there is still room for improvement. India would likely see the greatest improvements in its GHI scores and ranking, as well as in the on-the-ground well-being of its children, by addressing its high rates of child wasting and child stunting. India’s child wasting rate, at 18.7 percent, is the highest of any country in the report, and its child stunting rate, at 35.5 percent, is the 15th-highest in the report. Of course, a decrease in India’s GHI score does not guarantee an improvement in its ranking if other countries reduce their GHI scores by equal or greater amounts. For India to improve in the ranking, it would need to improve more than other countries in the report. It is important to remember that the rankings in GHI reports cannot be validly compared from year to year (see #4).

In the compilation of the stunting and wasting values, we prioritize and use survey estimates that have been vetted for inclusion in the Joint Malnutrition Estimates and/or the WHO Global Database on Child Growth and Malnutrition, wherever possible. The GHI uses the same data sources for all countries to calculate the respective country scores. This ensures that all the rates used have been produced using comparable methodologies. Introducing exceptions to this process for any country or countries would compromise the comparability of the results and the ranking. We would be glad to consider the inclusion of the Poshan tracker data for future editions of the GHI once they have been included in the UNICEF-WHO-World Bank Joint Malnutrition Estimates Joint Data Set of Survey Estimates and/or the WHO Global Database on Child Nutrition.